Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Between 2001 and the beginning of 2018, more than 1,500 U.S. military service members lost limbs in the line of duty. Although technology has improved the prosthetic devices these people can use, a stubborn obstacle remains: the fragility of human skin.

“Skin was never meant to hold this kind of pressure,” says Lee Childers, the senior scientist for the Extremity Trauma and Amputation Center of Excellence at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas.

“Think about it like a blister on your foot. It’s painful, but you can still get by,” he continues. “In an amputation, it’s a blister on your residual limb. You can’t use your prosthesis until the blister is completely healed. If it’s your leg [that is affected], you can’t walk for two or three weeks. Think about how that would impact your life.”

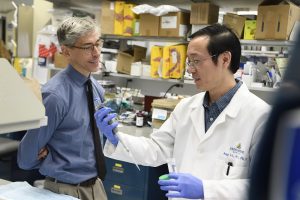

What if there were a way to make the skin at an amputation site tougher, like the palm of your hand or the sole of your foot? Luis Garza, an associate professor of dermatology at Johns Hopkins and leader of the Veteran Amputee Skin Regeneration Program, is developing a cell therapy that could enable prosthetics wearers to use their devices longer.

“This is an example of personalized medicine. We’re taking each person’s own cells, growing them up, and inserting them back in,” Garza says.

Garza’s postdoctoral research focused on skin stem cells. In 2009, he and his department chair, Sewon Kang, began having conversations about how that work could help the increasing numbers of Veterans coming back from war with amputations. Garza and his team received grants from the U.S. Department of Defense, National Institutes of Health, and Maryland Stem Cell Fund that have moved the program forward in the past decade.

Garza’s team spent the summer of 2019 testing “normal” subjects — those without amputations — to perfect the procedure, including the dose, content, method, and frequency of the injections. During one appointment, members of Garza’s team took biopsies of skin from a subject’s scalp and sole. The cells went to a lab where they were grown under an FDA-approved protocol and passed through quality control tests. In a second appointment, subjects completed a questionnaire and underwent baseline measurements of their skin’s thickness and strength. Garza’s team then injected a site on the subjects’ skin with the stem cells grown from their cells in the lab.

“We’re hoping that these stem cell populations will engraft in the new skin,” Garza says.

The subjects returned to Hopkins several months later to go through the questionnaire and measurements once more, and Garza’s team documented changes.

Confident in the results they gleaned from the normal subjects, Garza’s team enrolled its first subject with an amputation in August. Moving from the normal population to the amputation-affected population quickly unearthed some aspects of the therapy Garza didn’t anticipate.

“When we talked with him, he said ‘I don’t want to mess with my one remaining foot – do you have to take skin from there?’ And we said, ‘Actually, no, we could do your palm,’” Garza says. His team then tested the biopsy and growth of palm cells from subjects in the normal population. “We’re moving away from having our product informed purely by biology to letting our therapy development be shaped by the user.”

Although federal grants have supported much of the program’s progress, private philanthropy has played a role, too. Corporations like Northrop Grumman, foundations like the Alliance for Veteran Support, and grateful patients with and without ties to the armed forces have contributed nearly $300,000. Those gifts have enabled the program to persevere through gaps between federal grants.

Private funds will be increasingly important as the project enters its next phase: extension to military medical centers around the country. Garza’s team must prove that the safeguards to protect cells on their round-trip voyage from a test site to Hopkins are effective. They also must secure approval by local institutional review boards for clinical studies.

“Soldiers are used to getting orders, but you can’t order someone to be part of a [medical] study,” Garza says. “There are hard medical ethics questions around how to make this open to them but ensure they don’t feel obligated. We’ve been working on that for a year, and we probably have another six months or so to go.”

Childers stands ready for whenever the program’s extension is a go. He will lead the study at Brooke Army Medical Center and feels motivated by the prospect of helping many of the Veterans he works with every day.

“We do everything we can to serve those who serve us. This can enable people to return to duty and be redeployed if they choose,” he says. “This is game-changing technology that will have an impact for our service members, but also others who live with amputation.”

That population includes the hundreds of thousands of Americans who’ve undergone amputations for complications of diabetes, who must use a wheelchair, or who wear ankle or foot orthoses for help with walking, among others.

“Having the ability to transform skin anywhere you want to target on the body will have gigantic implications across the entire spectrum of our society in many ways,” Childers says.

There’s a lot of work to be done before such benefits reach the public, Garza cautions. With continued support from donors and the military community, though, he’s optimistic about the program’s future.

“The challenges are pretty big, but I think within five years, it could happen,” he says. “That’s the hope.”

Disclaimer: The view(s) expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of the Army, the Department of the Air Force and Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Topics: Corporations, Foundations, Friends of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Fuel Discovery, Promote and Protect Health