Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

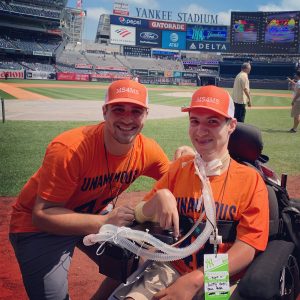

At a time when many of his peers were focused on planning graduation parties and securing first jobs, Sam Greenberg centered his attention on something less traditional — establishing a nonprofit that leverages the power of sports to fund multiple sclerosis (MS) research.

“It was the perfect storm of ideas as I was finishing college,” Greenberg remembers. “The more I shared the idea of using sports as a platform to raise awareness for MS, the more people got behind me.”

Greenberg founded Mission Stadiums for Multiple Sclerosis (MS4MS) in honor of his grandmother, who had MS, in 2011. The nonprofit hosts a mix of in-person and virtual events to fund research and provide financial support for people living with the disease. MS4MS also assists individuals across the country in hosting their own fundraising and awareness events to support the organization.

For the last several years, MS4MS has partnered with the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerosis Precision Medicine Center of Excellence (MS PMCOE) to support cutting-edge research into MS therapies and outcomes. The donations started small, about $2,000, but have quickly grown. Last year, MS4MS donated $100,000 to the center, and the organization has given more than $152,000 in total to fuel investigation into the disease.

“When you say ‘Hopkins MS Research,’ the name holds a lot of weight and value,” Greenberg says. “But more than that, the people inside the center brought us in as an extension of their team in a sense. They’re hands-on; they attend our events. I chose them originally because of their reputation, and I’ve continued to partner with them because of the relationship that they continue to build with us.”

Ellen Mowry — professor of Neurology, co-director of the MS PMCOE and the Multiple Sclerosis Therapeutics Program, and chief medical officer for Johns Hopkins inHealth, a strategic initiative to advance precision medicine at Hopkins — serves on the board of MS4MS. She says her involvement with the organization helps her get perspectives outside of her day-to-day work.

“In talking to loved ones of people with MS or people with MS who are not your patients, you can connect in a different way,” she says. “That’s just engaging and wonderful.”

Mowry also appreciates the organization’s emphasis on movement, as her research is focused on keeping bodies healthy to improve outcomes in people with MS. MS impacts myelin, the coating around the nerves that helps them conduct impulses, and the underlying nerves that normally help with movement. Early symptoms can come and go, including vision and mobility impairment, sensory loss, burning pains, tingling, or bladder symptoms. As the disease duration increases, patients can experience increased, progressive difficulty in movement, particularly walking.

Diagnoses have increased in last 30 years, especially in women, and it’s now estimated that more than 20 million people worldwide are living with the disease.

Thanks to funds from MS4MS, researchers are looking for new ways to measure people’s clinical level of disability using wearable technologies, which Mowry describes as “research-grade wrist-worn activity trackers that record how people are living in their real lives.” The wearables provide researchers and clinicians with a more comprehensive look at patients with MS than traditional neurologic exams, which only show a snapshot of a person’s day. MS4MS has also helped fund work in analyzing and interpreting those data.

“The scope of the projects that we can do increases, but the spirit is still the same,” Mowry says. “It’s enabling some risk-taking in research that might not otherwise be possible.”

Researchers are also using the funds to develop new tools and purchase state-of-the-art equipment, which help anticipate how the disease is likely to progress and inform treatment. There are more than 200 genes associated with developing MS, and researchers are studying blood biomarkers to better predict outcomes, monitor the disease, and provide the best treatment options. The center has also been able to invest in new technology called optical coherence tomography (OCT), which images the back of the eye as part of routine MS assessment to assess microscopic nerve damage.

“MS is the one neurologic disease that affects people when they’re young, presenting in their twenties and thirties,” explains Peter Calabresi, a professor of Neurology, co-director of the MSPMCOE and director of the Division of Neuroimmunology and Neurological Infections.

MS researchers believe people respond to treatment better when they’re younger because of the brain’s plasticity. As patients age, the chronic microscopic damage accumulates.

“After about 10 or 20 years of treatments, it became clear that the disease was still progressing in a lot of patients. There’s a second stage of the disease, after age 40 or 50, when people slowly get worse,” Calabresi adds. “We’re trying to predict who is going to get that severe, disabling, progressive form of MS. We have some people who go 40, 50 years with the disease and never end up with much disability at all.”

Because MS is a complex disease that involves genetic predisposition and environmental factors, similar to cancer, treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all. Biomarkers and imaging help clinicians determine what therapies will be most effective against the disease without negatively impacting the patient.

“The ultimate goal is for researchers to say, ‘We have a cure for MS,’” Greenberg says. “The reality of that is difficult. So we just take it one step at a time with that end goal in mind. We’re in it for the long haul to help people with MS from beginning to end and provide a platform that’s fun and engaging.”

Topics: Friends of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Neurology, Fuel Discovery, Promote and Protect Health