Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

A few days before a hockey tournament, then-13-year-old Bryan Jackson could barely walk. His parents rushed him to the ER, where doctors discovered a low-grade glioma — a benign, slow growing tumor originating in the glial cells that support neurons in the brain. Three surgeries left him with limited mobility on his right side.

“It sidelined him from hockey, which was everything he loved,” says his mother, Debbie.

Lauren Loose, now 27, was born with neurofibromatosis type 1, a genetic condition that caused her to develop low-grade gliomas.

“She was on different chemotherapy protocols and clinical trials from just before her second birthday through age 11,” says her mother, Marianne.

Both families found support and inspiration from their sports communities. The hockey community in upstate New York rallied around Bryan as he adjusted to life after treatment. Lauren’s dad, John, is a college football coach, and their extended football family stepped up to help.

The Jacksons started an annual women’s ice hockey tournament called Stick It to Brain Tumors, which has raised more than $300,000 for pediatric brain tumor research, including more than $160,000 for research at Johns Hopkins. The Looses established Lauren’s First and Goal Foundation, which has raised $2.87 million, with $544,500 going to Johns Hopkins, through football camps and virtual coaching clinics.

The funds are designated to support the Brain and Eye Tumor Lab in the Department of Pathology, which focuses on low-grade glioma research and is led by Charles Eberhart and Eric Raabe. Low-grade gliomas are the most common pediatric brain tumors, but research funding is scarce compared with more aggressive tumors. Mortality rates in patients with low-grade gliomas are low, but morbidity is high owing to their sensitive locations and the severe side effects of standard treatments, which can include a combination of neurosurgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

Sustained philanthropy from organizations like Lauren’s First and Goal and Stick It to Brain Tumors “kept us working through repeated years of trial and error,” Eberhart explains. “There is great potential for philanthropy to move the needle in targeting the disease and developing new cell-based models for drug testing.” Cell models developed by Eberhart and Raabe’s lab are made available around the world through a National Institutes of Health repository.

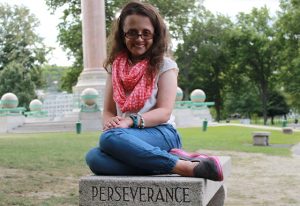

Bryan’s and Lauren’s stories share another common thread: perseverance. Bryan, now 35, eventually learned to walk with a brace and get by with his left hand. He earned a master’s degree and now works for a development firm that provides affordable housing.

“To me, he’s my hero,” his mother says.

Lauren spends summers working in a nonprofit cafe that employs people with disabilities.

“She takes such pride in her job there,” Marianne says. “It’s really been transformative for her.”

Topics: Friends of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Fuel Discovery, Promote and Protect Health