Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

The year was 1960, and Ingrid Rose (née Roessner) was running late for her French Civilization class at the Alliance Française in Paris, France. She darted into the classroom and took the only available seat next to a man who, upon noticing an American magazine sticking out of her coat pocket, addressed her in English. The man was Milton Rose, then stationed with the U.S. Army in Fontainebleau, outside of Paris. The conversation he began with Ingrid would last a lifetime.

Milton grew up in Romania, but was fluent in English through his American father. He often borrowed and exchanged books from the American and British Embassy libraries. This drew suspicion from the post-War Communist authorities and Milton was arrested in 1946 while taking soup to his dying father. He was put in a labor camp working on the Danube-Black Sea Canal. Milton claimed to know how to weld in order to receive food rations, so he worked as a welder on the Canal.

After his tour in France, Milton attended the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, and continued his military service in Frankfurt/Main, Munich, and then Baltimore where he was discharged in 1967. By that time, Milton and I were married and we decided to move from Baltimore to Washington, D.C., where he worked for the departments of the Interior and Commerce, while I became an employee at the European Community Information Service. During the Cold War Milton worked with the Department of State in Poland and Romania where I trained as a paper conservator in Warsaw and engaged in microscopic research of paper fibers and pigments.

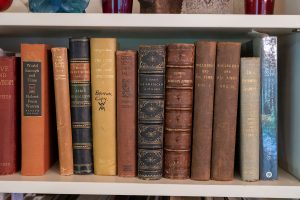

It’s important to me that our collection is well taken care of. The Sheridan Libraries has an amazing group of conservators and professors who understand the history and significance of books, prints, and art.

Once settled in D.C., we got involved in print collecting with the Washington Print Club, and our interest in works on paper really took off. When we discovered that original prints and illustrations were being removed from books and sold separately, we made it our mission to buy and preserve as many as we could. During that period of collecting and associating with printmakers, I compiled the catalogues raisonnés of printmakers Werner Drewes and Prentiss Taylor.

In late 2000 Milton was diagnosed with leukemia which went into brief remission, only to reappear in early 2001. By 2007, we were told that there was no longer any hope of his getting well again. Aware of clinical trials at Johns Hopkins, we asked to participate in one, and that is how we met Dr. Judith Karp, then at Kimmel. With her team she took Milton under her wing and, against the odds, resurrected his health, improving the last six months of his life during which he regained some strength and his “joie de vivre.” I am forever grateful to the Kimmel Cancer Center and Dr. Karp for giving us those last six months.

When I was diagnosed with age-related macular degeneration, it became necessary to seek a second opinion. I was referred to Dr. Adam Wenick, who was very honest, which prompted me to include Wilmer in my will. Dr. Wenick continues to monitor and treat my eyes. Through these medical challenges, I became aware of the high ethos at Johns Hopkins Medicine and am most grateful to its practitioners. It gives me real pleasure to close the circle of our 1966 beginning in Baltimore and my working as a research assistant for a children’s health study at Johns Hopkins by including Kimmel and Wilmer in my will in memory of Milton. Thank you, Johns Hopkins Medicine!

This story first appeared in the Summer 2023 edition of Planning Matters.

Interested in partnering with Hopkins to plan your legacy?

Topics: Friends of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Sheridan Libraries and University Museums, Fuel Discovery, Strengthening Partnerships