Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

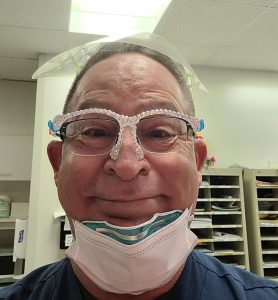

In 2020, Rick Caporin’s life as a psychiatric nurse in Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Emergency Department and as a single father was upended by COVID-19. The constant changes in hospital protocols and the sudden homeschooling of his four children turned his already stressful life into “a tornado.” So that fall, when enrollment began for the Mindful Ethical Practice and Resilience Academy (MEPRA), he signed up.

“It blew my mind, the way it helped me look at situations in a different perspective,” he says. “I felt like I was being suited up with armor to face work, to face day-to-day life.”

A 12-week educational program, MEPRA is a part of a growing body of research into moral distress — the inability to act in alignment with one’s moral values — led by Cynda Rushton, the Anne and George L. Bunting Professor of Clinical Ethics at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics and the School of Nursing. Program participants learn mindfulness, values clarification, self-stewardship, and analytical tools that better prepare nurses for the ethical challenges they often face daily in a hospital setting. They then have the chance to put those techniques into practice with actors who simulate real-world clinical situations.

We talked with Rushton in 2017 when she had begun the program and recently caught up with her to learn more about her studies in moral distress and new resources for addressing it.

Follow-up research by Rushton and her colleagues has found that MEPRA participants sustained benefits from the program for at least six months. The implications are profound for an essential health care field that has seen a mass exodus during COVID-19.

“Nurses have borne physical, emotional, and moral burdens in ways other people haven’t in this pandemic because of their proximity to patients,” Rushton explains. “Many of these issues were present before, but it has intensified in a way that has profound consequences to our profession and have to be looked at from a systemic perspective.”

Rushton and her colleagues developed additional programs and resources to aid hospitals, nurses, and researchers. One is the Rushton Moral Resilience Scale, which helps heath care professionals self-evaluate their level of moral resilience, allowing them to track changes over time and give insight to which components can be amplified. Funded by the Dorothy Evens Lyne Fund and free to use, the scale has grown to have an international reach, with requests for it coming from Brazil, Turkey, Portugal, and the Netherlands, and translations being made to make it accessible to a global community of nurses.

Rushton also spearheaded The Nurse Antigone, made possible through a collaboration between the Theater of War Productions, the Berman Institute of Bioethics, the School of Nursing, and the Resilient Nurses Initiative in Maryland. Performed over Zoom, professional actors, nurses, and even author Margaret Atwood perform Sophocles’ Antigone, the ancient Greek play about a young woman who sacrifices her life for what she believes is morally right.

Following the performance, a panel of nurses discusses ways the play’s themes resonate with their occupation. The first of the 12 free public performances on March 17 saw more than 3,000 attendees and received overwhelmingly positive feedback from nurses who appreciated how the play acknowledged their experiences of occupational grief, loss, and ethical challenges in the pandemic.

This type of work has never fit into typical funding mechanisms. The Nurse Antigone project, MEPRA, and Rushton’s professorship are only possible through individual philanthropy.

“Philanthropic support is absolutely the catalyst for all of this, and I can’t even begin to say how grateful I am,” says Rushton.

In response to the further research and feedback they’ve received, Rushton and her colleagues plan to publish an updated version of the Moral Resilience Scale and a second edition of Moral Resilience: Transforming Moral Suffering in Healthcare, which remains the only book on the topic of moral resiliency.

“Right now, we are taking what we’ve learned to see how it can best serve nurses now, how we can be part of healing the profession, and also create a vision for the future.”

One of Caporin’s biggest takeaways from MEPRA was a sense of a community with his cohort, despite everyone coming from different units of Hopkins. He views Rushton as a role model, and he’s become an advocate for MEPRA, aiming to bring her sense of calm and community back to his own unit.

“I’ll lead meetings, and someone will ask me, ‘Could you begin it with a MEPRA moment?’ And I’ll spend 15 minutes going through a group meditation like Cynda did with each session,” he says. “It helps everyone defuse their tensions, and you can see a visible difference in people.”

Topics: Alumni, Faculty and Staff, Friends of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Berman Institute of Bioethics, School of Nursing, Fuel Discovery, Promote and Protect Health