I always found that matching gifts usually create a lot of interest and a lot of excitement. They generate some pretty neat things if they’re done properly.”

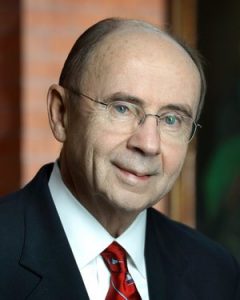

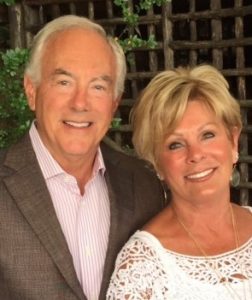

Ross Myers Matching donor to the Brady's hereditary prostate cancer program

Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Researchers at Johns Hopkins’ Brady Urological Institute are working to uncover the genetic mutations responsible for prostate cancer in an effort to study the heritability of the disease, which especially impacts men of African descent.

“There are 25,000 genes that are responsible for making proteins,” explains University Distinguished Service Professor of Urology and Chairman Emeritus of the Department of Urology, Patrick Walsh, MD. “And what we are looking for is the equivalent of one misspelled word in 20 sets (400 separate volumes) of the Encyclopedia Britannica.”

Walsh began studying hereditary prostate cancer in the late 1980s. Along with Bill Isaacs — the William Thomas Gerrard, Mario Anthony Duhon, and Jennifer and John Chalsty Professor of Urology — they set out to determine the genetic influences for the development of prostate cancer, why prostate cancer occurs in some men but not others, and the genetic determinants of metastatic prostate cancer through genetic sequencing.

Historically, gene mapping has been prohibitively expensive. In recent years, though, the technology has become much more accessible, and Hopkins researchers are digging even deeper into the genetics of prostate cancer.

“We have a treasure chest of genes that we’ve collected over 30 years, and our goal is to carry out whole exome sequencing in families,” Walsh says. “We’re looking in places that no one has ever looked. We’re hopeful that, with further analysis, we’ll uncover multiple candidate genes that were not previously implicated and understand their role in the development of prostate cancer.”

When one of Walsh’s patients and his wife, Ross and Beth Myers, learned of the exploration into the heritability of prostate cancer, the most common form of cancer in men, they were eager to support the work. Myers was 49 when he was diagnosed with the disease in 2002. He lost an uncle to prostate cancer and worries about his three sons, who are now in their 40s.

“Everybody thinks it’s just an old man’s disease. Well, that’s not necessarily true. It’s a male issue. And so, to me, it’s interesting research,” Myers says.

The Myers proposed a matching gift for the $4 million project — $2 million if the Brady could raise the remaining $2 million for the research.

“I can’t think of a better person in the world to be passionate about something and get something meaningful done than Patrick Walsh,” Myers explains. “Any time I’ve ever gotten involved in fundraising, I always found that matching gifts usually create a lot of interest and a lot of excitement. They generate some pretty neat things if they’re done properly. I thought that would be the best way to help get this thing kicked off.”

Researchers have already uncovered a number of genes that are important in identifying men who are at risk for developing prostate cancer. Like breast cancer, there is a panel of genes associated with prostate cancer that can be sequenced from a blood or tissue sample. These genes can identify men at higher risk of the disease, explains Isaacs, who developed the most recent plan to examine the unique genetic variants that cause prostate cancer.

“It is a really big deal to have a marker for men who are at risk of potentially lethal prostate cancer that you can find before the cancer even appears,” Isaacs, SOM ’84 (PhD), says. “One of the main reasons we are interested in this germline genetic approach — studying genetic material passed from parent to offspring — is to identify men either at risk of prostate cancer or at risk of an aggressive disease before they have a cancer that’s no longer operable.”

I always found that matching gifts usually create a lot of interest and a lot of excitement. They generate some pretty neat things if they’re done properly.”

Ross Myers Matching donor to the Brady's hereditary prostate cancer program

Though common in multiple populations, men of African descent are at higher risk of being diagnosed with and dying from prostate cancer. Isaacs says the problem is multifaceted — in addition to social and economic issues, such as disparities in health care and lack of screening, early data suggest genetics are also involved.

“There are genetic variants that predispose to prostate cancer, which are novel or present at higher frequencies in men of African descent,” Isaacs says.

Myers hopes the gift will enable researchers to explore germlines not only to identify what genes cause the disease, but also determine the best type of treatment for men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Though surgery has traditionally been one of the primary treatments, Walsh and his team have pioneered alternative options for treating non-life-threatening forms of the disease, which Isaacs says has been one of the key advances in urology and will benefit from a better understanding of the genes behind prostate cancer.

“There will be less trauma and far less financial cost,” Myers says. “It’s also going to save lives. It’s going to save a lot of pain, suffering, and worry. Cancer affects your whole family. I know that the research will produce something very meaningful.”

The Brady is just $200,000 shy of reaching the $2 million match goal. Elissa Kohel, the Brady’s director of development, says the significant philanthropic support the Myers have provided through their matching gift is “nothing short of transformational” and has encouraged others to give.

“Their gift has inspired new donors to become involved, re-energized existing supporters at all giving levels, and sparked a renewed interest in the field of hereditary prostate cancer, something we haven’t seen in many years,” she adds.

To date, the match has motivated more than 55 other donors to give to the program.

Topics: Friends of Johns Hopkins Medicine